For the 17th year, Wellfleet hosted its State of the Harbor Conference. It was held at the Wellfleet Elementary School on a beautiful, sunny, fall day––Saturday, November 2, 2019.

Participants included ordinary citizens, fishermen, students from K-12 through graduate school, town officials, and staff of the Mass Audubon, the National Park Service, the Center for Coastal Studies, Wellfleet Conservation Trust, and other organizations. They came to report on what they are learning about the ecosystem of the harbor.

Audience at Wellfleet Elementary School

Abigail Franklin Archer, from Cape Cod Extension, was the Conference Moderator. The schedule was filled with interesting presentations and posters.

There was coffee, snacks, and ample time for informal discussions as well. Americorps workers focusing on the environment helped with the organization, logistics, and even serving Mac’s clam chowder for the lunch.

Q/A with Martha Craig and Kirk Bozma on Herring River restoration

On Sunday, there was a follow-up field trip to look at Wellfleet Harbor’s history and its “black mayonnaise”.

Interactions Within Ecosystems

As was the case in previous years, this was a learning event throughout.

Continuing what’s now a 17-year tradition, the conference showed the complex connections between humans and other living things including phytoplankton, striped bass, menhaden, horseshoe crabs, oysters, quahogs, seals, terrapins, molas (sunfish), phragmites, bacteria, protozoa, resident and migrating birds, as well as the land, sea, and air.

Presenters discussed ideas that went beyond the everyday understanding of harbor ecosystems. These ideas included bioturbation––the disturbance of soil, especially on the sea floor by organisms such as crabs and other invertebrates. There was talk of organism lipid levels as a measure of their nutrient value for predators. One poster emphasized the rise in Mola mola population attributable to increased numbers of jellyfish.

John Brault with Krill Carson’s poster on the Mola explosion

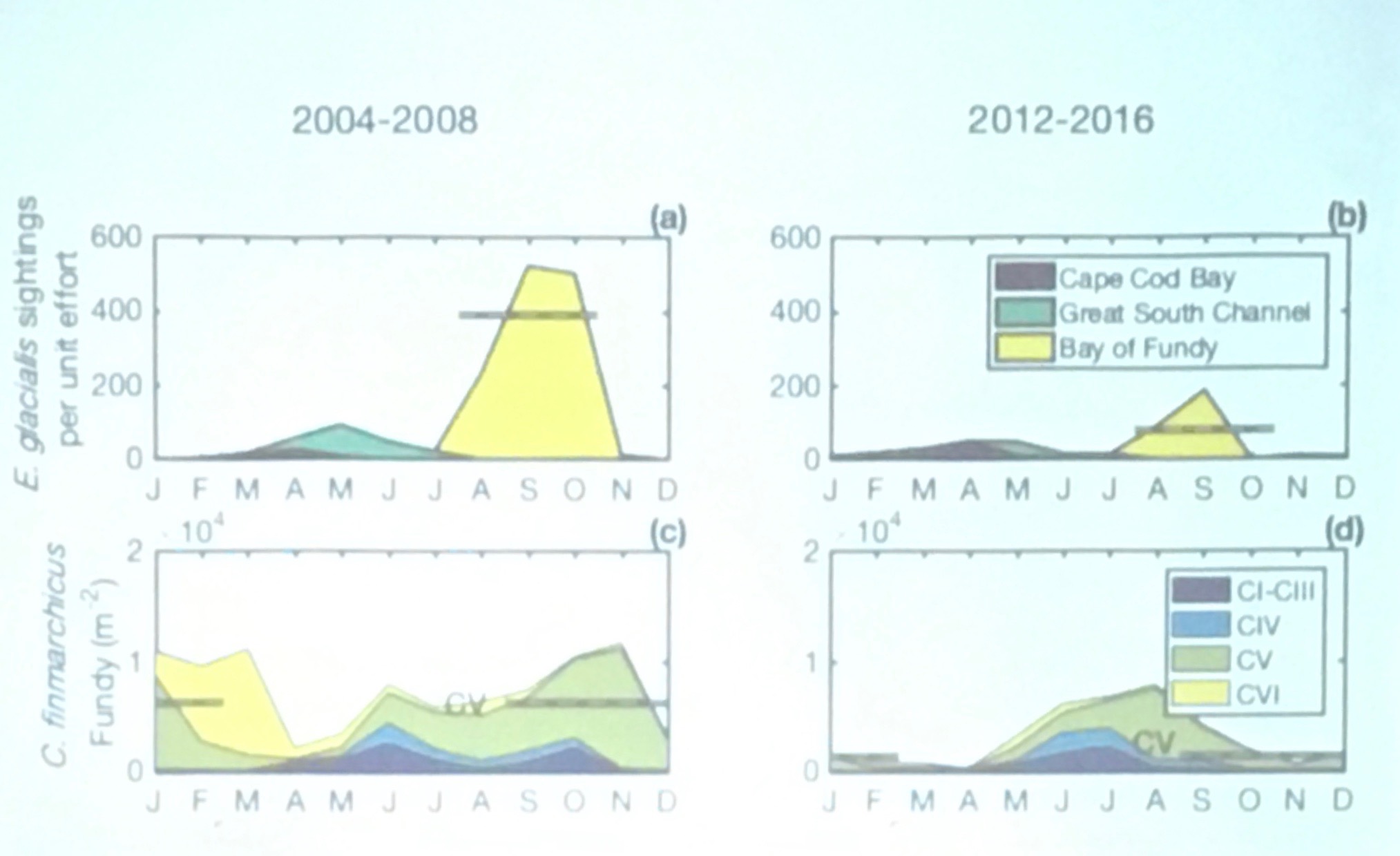

One presentation discussed a major meta-analysis of ocean phenology studies. This research looks at when significant events such as spawning, migration, or molting, occur in an organism’s life cycle. Those times are shifting as a result of global heating, changes in ocean currents and nutrient availability. In some cases there are critical mismatches between the cycle for a predator species and its prey, which has major consequences for both and for the larger ecosystem. A population may increase earlier than in the past, but its food source doesn’t necessarily match up with that.

Correlating sightings of right whales with copepod density

Most notably, the Conference considered the impact of these diverse aspects of nature on people and vice versa. In every presentation or poster, one could see major ways in which human activity affects other aspects of nature.

Civic Intelligence

The Harbor Conference is a good example of how to improve what Doug Schuler calls civic intelligence, becoming more aware of the resources in our community, learning of its problems, finding ways to work together, and developing civic responsibility.

In any locality, civic intelligence is inseparable from the nature all around. But in Wellfleet this connection is more evident than in most. Every issue––transportation, affordable housing, employment, health care, fishing and shellfishing, waste management, history, and more––affects and is affected by our capacity to live sustainably. The harbor and the surrounding ocean, rivers, and uplands are deeply embedded with that.

There is a depressing theme through much of the Conference. The studies reported in detail on the many ways that humans damage the beautiful world we inhabit, through greenhouse gas emissions causing global heating and higher acidity, increased storm activity, and sea level rise. There is pollution of many kinds, black mayonnaise, and habitat destruction.

Mark Faherty offered a promising note for the horseshoe crab population. But even it has a downside: As the whelk population falls there will be less call on horseshoe crabs as bait, so that may help their recovery.

Nevertheless, it is inspiring to see the dedication of people trying to preserve what we can, and to learn so much about the ecology of the unique region of Wellfleet Harbor.

Maps for Learning

A striking feature of every presentation and poster was the use of maps. These included maps showing tidal flows, migration patterns, seasonal variations, sediment accumulation, human-made structures, and much more.

Maps of process and monitoring

If we extend the idea of maps to visual displays of information, then it evident that even more maps were used. These included flowcharts for processes such as the one for adaptive management shown above, organization charts, and timelines for events in temporal sequences.

1887 Map of Wellfleet

The maps are not only for communication of results. They are also a useful tool for the research itself. The most useful applications involved overlays of maps or comparisons of maps from different situations or times.

As an example, the population of horseshoe crabs could be compared with the management practices in a given area. Is the harvest restricted to avoiding the days around the new and full moon? Can they be harvested for medical purposes? For bait? The impact of different regulatory practices across time and place could easily be seen in graphical displays.

The Conference as a Site for Learning

You would find similar activities at many conferences. But the Harbor Conference stands out in terms of the cross-professional dialogue, the collaborative spirit among presenters and audience, and the ways that knowledge creation is so integrated with daily experience and action in the world.

This learning is not in a school or a university; there are no grades or certificates of completion. There are no “teachers” or “students” per se. However, by engaging with nature along with our fellow community members, conference attendees explore disciplines of history, statistics, politics, commerce, geology, biology, physics, chemistry, meteorology, oceanography, and more.

Nature itself is the curriculum guide. It is also the ultimate examiner.

[Note: This text will be cross-posted on the Wellfleet Conservation Trust blog.]

We talked about the issue of importing ideas from abroad. But there are impressive things underway here in schools, colleges, and informal learning that could be a model others around the world.

We talked about the issue of importing ideas from abroad. But there are impressive things underway here in schools, colleges, and informal learning that could be a model others around the world. But that all happened better than I expected. The reality went beyond the original plan and came to include multiple organizations, trips to excellent schools, and the creation of PENN.

But that all happened better than I expected. The reality went beyond the original plan and came to include multiple organizations, trips to excellent schools, and the creation of PENN.