Band saw in the restored factory

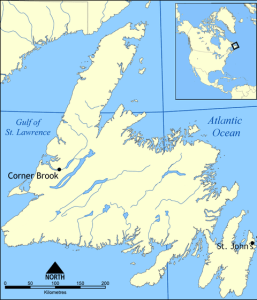

Port Union is a gem that I knew nothing about. It seems little understood by Wikipedia or Google searches, or even many locals. Yet it’s a fascinating site and story, and an important one for anyone interested in workers’ rights or community building. The new museum and other facilities are well worth a visit, even if you have no interest in dramatic seascapes, quaint Newfoundland port towns, Ediacaran fossils, handmade crafts, or beautiful nature walks.

The town claims to be the only union-built town in North America. Some others might quibble. For example, Nalcrest, Florida was conceived, designed and financed by the letter carriers union as an experiment in retirement housing. Cities such as Chicago and St.Louis are often described as “union-built towns.” But it’s hard to find examples anywhere of a town so fully conceived and established of, by, and for a union.

The founding of Port Union

William Ford Coaker, 1871-1938

William Coaker founded the town as the base for the Fishermen’s Protective Union in 1917. During 1908-09, he had travelled around Notre Dame Bay, seeking support for a union in each of the tiny communities. By the fall of 1909, the FPU had 50 local councils. By 1914, over half the fishermen in Newfoundland had become members.

In rapid succession, the FPU and the town established a trading company to break the merchants’ stranglehold on salt fish trade. They soon built workers’ housing, a retail store, a salt-fish plant, a seal plant, a fleet of supply and trading vessels, a spur railway line, a hotel, a power-generating plant, a movie theatre, a school, and a factory to build these facilities and other things the community needed.

Clamps for door making

There was much more, including even a soft drink (or ìtemperance beverage) factory. One of the most important enterprises was the influential Fishermen’s Advocate newspaper.

Reaction and decline

The anthem of the Fishermens Protective Union was sung at FPU meetings to show support for Coaker and his movement to unite the fishermen. It starts as follows:

We are coming, Mr. Coaker, from the East, West, North and South;

You have called us and we’re coming, for to put our foes to rout.

By merchants and by governments, too long we’ve been misruled;

We’re determined now in future, and no longer we’ll be fooled.

We’ll be brothers all and free men, we’ll be brothers all and free men,

We’ll be brothers all and free men, and we’ll rightify each wrong;

Computing scale used in the retail store

There was widespread support among the fishing communities for Coaker and the FPU. Coaker himself had a successful career in the Newfoundland House of Assembly and as minister of marine and fisheries through 1924.

But they union was attacked by moneyed interests and the Catholic church. Eventually, it lost power and its political role ended in 1934. The cod fishing moratorium furthered the community’s decline.

By the late 1990s, the town was no longer a commercial center and was in a state of neglect. In 1999, the original part of the town and the hydroelectric plant were designated a National Historic Site of Canada.

Questions and connections

I came away from Port Union with many questions. I’ve read that the FPU drew from and influenced the farmer’s co-operatives in the western provinces. I wondered though whether it was connected with enterprises such as La Bellevilloise in Paris, which was founded earlier, after the Commune. It was the first Parisian cooperative project to allow ordinary people access to political education and culture. It, too was a place of resistance with a “from producer to consumer” motto. There were similar projects in Ireland and England, which might have provided a more direct link for Coaker.

The Fisherman’s Advocate

Coaker lived nearly contemporaneously with Jane Addams. Although her settlement house work was not directly union organizing, it shared in the effort to provide self-contained services and to promote workers’ rights.

The earlier Toynbee Hall in London’s East End sought to create a place for future leaders to live and work as volunteers. It was created out of similar motives, and the realisation that enduring social change would not be achieved through individualised and fragmentary approaches. I’d like to learn more about how, if at all, these enterprises learned from one another.

What if

I’d also like to learn more about Coaker himself. Michael Crummey’s novel Galore includes Coaker as a major character. In an interview, Crummey describes the actual Coaker as an enigma and the FPU experience as a pivotal moment:

It is the great “what if” moment in our history. The entire story of 20th century Newfoundland would have been completely different if Coaker had succeeded. We might still be an independent country.

—

Even truncated as it was, what Coaker accomplished was extraordinary. Delegations from a number of Scandinavian countries came to study what he was up to and implemented many of the reforms in their own fishery that he was fighting for.