I used to imagine the bird of peace as a small white dove with an olive leaf in its mouth, like the one Noah sent out to see whether the waters had abated. But now I think it’s really the big city pigeon, which some people call the “rat with feathers.”

This change of image started when I heard about the improbable scheme of Bertrand Delanoë, currently the Mayor of Paris. Delanoë recognized a problem: Pigeons are messing on the beautiful statues and buildings of Paris, costing huge piles of euros and displeasing both residents and visitors. But there are pigeon-lovers as well, many of whom risk fines to share their day-old bread with the hungry birds. Is there any way to recognize the divergent needs of pigeons, pigeon-haters and pigeon-lovers?

The Mayor proposed something, along the lines of his beach on the Seine or the ice skating rink 95 meters up the Eiffel Tower. I learned later that people in Basel, and then throughout Germany, had this idea also, but initally it seemed crazy to me. I’m afraid that when I talked with others about it they attributed that craziness to me as well.

The idea was to build a home for the pigeons, a pigeonnier, where they could live comfortably and safely, and even be fed by the pigeon-lovers. This would preserve “the only sign of biodiversity in the city center.” In return, the pigeons would not mess the statues and they’d undergo population control. The money saved on cleaning statues would pay for the €40,000 construction and €9,000 annual maintenance.

The idea was to build a home for the pigeons, a pigeonnier, where they could live comfortably and safely, and even be fed by the pigeon-lovers. This would preserve “the only sign of biodiversity in the city center.” In return, the pigeons would not mess the statues and they’d undergo population control. The money saved on cleaning statues would pay for the €40,000 construction and €9,000 annual maintenance.

Some people asked rude questions, such as “what will make the pigeons stay near their houses?” or “how can their population be controlled?” Yet the pigeonnier had been built and more were promised. I had to see for myself.

I set out for the Place de la Porte de Vanves in the XIVème arrondissement. This is in the SW of Paris, near the Périphérique, so it meant a good walk, and as I’ve discovered many times in Paris, a walk that would take on its own character.

Along the way, I stopped briefly in the Jardin de Luxembourg. On the west side of the garden, near rue Guynemer, I looked for a while at the bronze model of the Statue of Liberty by Frederic Auguste Bartholdi. The statue itself was given by France to the United States in honor of our first centennial. Next to the model was an oak tree, planted to commemorate the solidarity of the French and Americans in response to 9/11. These made me ponder the deep intertwining of French and US histories, as well as the current political divisions. But I couldn’t dewll on that, as I had a goal—to see the pigeons in their new home.

Walking a bit south of the garden, I came upon the unusual sight of a man getting into a late-model car and driving away. What caught my eye was that he wore sandals and a brown robe with a rope around the waist. He was a Capuchin monk coming out a monastery, next to Notre-Dame de la Paix, at 6, rue Boissonade. The image of old and new, religious and secular, somehow seemed relevant to my ponderings on the French/American relations, to accommodating and understanding differences, especially next to the “our lady of peace” church, but again, I had a goal to pursue, and couldn’t afford to linger there.

Walking along rue Schoelcher, I passed Montparnasse Cemetery. There were plaques describing Victor Schoelcher (1804-1893), best known for the decree of April 27, 1843 abolishing slavery in the French colonies. Reading more about him, I learned of how he became the most well-informed French person on the Caribbean colonies, and of his efforts to show how sugar production could be continued without relying on slaves. He helped the French people see that their interests in peace and well-being were not counter to justice, but in fact depended upon it. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

But I moved on, not relinquishing my goal of seeing the pigeons in their house. At the town hall of the XIVème arrondissement, at 2, place Ferdinand Brunot, I stopped briefly at one of those innumerable monuments to the “enfants mort pour la france” (the young people who died for France). If I were ever to lose a loved one to war, I would certainly want to believe that it was for something noble, but I wondered, especially having just visited the battlefields of Verdun, whether all those deaths were really for France, or instead, for greed, stupidity, injustice, the inability to see from the perspective of others, and all the other vices that foster wars and violence.

Still moving toward my goal, I walked along rue Didot to the Cité Croix Rouge. This is a reconsturction of the Broussais charity hospital, which is to become “un grand projet humanitaine du couer du XIVème” and “un lieu d’échanges ouvert à tous.” This new Red Cross center will be open to all and serve 1000 people a day as a hospital and education center. It seemed like a grand and noble project, but I couldn’t avoid seeing the graffitti and tags marring the large banner proclaiming the project. I wondered about whether the “writers” were the intended beneficiaries of the Cité Croix Rouge and about the difficulties of working for the justice that Schoelcher and others saw as so necessary to civil society.

On other walks, I’ve focused on architecture or art, music, history, science, the clothes, or most often, the ordinary people on the street. This one presented me with images of peace and justice, which I hadn’t intended. I simply wanted to see the folly of the pigeon house.

Nevertheless, I reached my goal, and was able to see it in a way I hadn’t expected. The pigeonnier was set in a small park, with benches and trees. Pigeon-lovers could watch the pigeons and even feed them there. Pigeon-haters could stay away, or perhaps learn that pigeons aren’t so bad when they have a place to live without harming others. The pigeons seemed happy, too. I also realized that the Place de la Porte de Vanves had become a more humane place. Softening the nearby railroad tracks, construction projects, and its general gritty urban character, the little park offered a hint of the natural beauty and gentility I had felt earlier that day in the Jardin de Luxembourg. I learned from the Pigeon Control Advisory Service that killing pigeons simply doesn’t work; they breed too fast, and attempting to kill them all simply helps them evolve into stronger, faster, smarter birds. I don’t know whether providing comfortable, modern homes, with ample food and water, perch sites, and a garden nearby will work either, but I saw that there was something grand, not just foolish, in the idea.

Jane Addams showed that tragedy lay in “believing that antagonism is real,” in assuming that a gain for one must mean a loss for the other. In contrast, the pigeonnier represents an attempt to realize what she called “affectionate interpretation,” to see the world as others see it, and thereby, achieve progress toward a common outcome. Pigeons need food and water, and a safe place to live and rear their young. But they don’t need to mess up the statues. Similarly, pigeon-lovers, pigeon-haters, Parisians, and visitors each have their own needs and interests, which need to be understood and accepted, rather than quashed. The pigeonnier and its park is a common good, which is based on interpreting each party in an “affectionate” way. In fact, no one’s interest is served either by killing pigeons or by indiscriminate feeding.

The final story of the Paris pigeonniers remains to unfold. But regardless of the outcome, it stands as a lesson for larger conflicts. Many people assume that their interests are served by military force or by building walls, indiscriminately imposing their interests over those of others (consider US prisons, immigration policies, the war in Iraq, etc.). The tragedy here is not just that injustices are done, that we commit these injustices on ourselves.

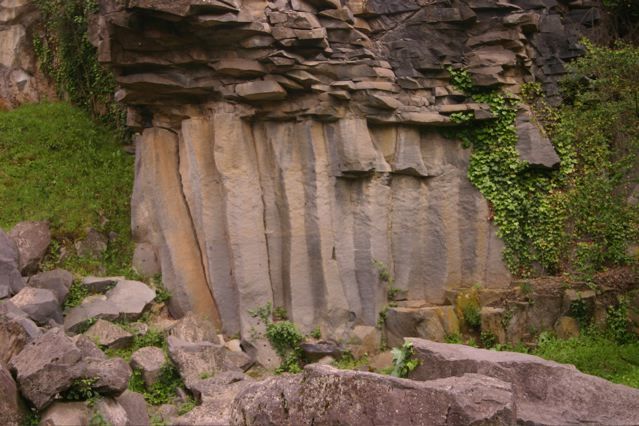

The photo on the left is from the Route of Les Tres Colades, with its spectacular basalt cliffs. It shows the results of the cooling of the lava as it flowed towards the site of what is now Sant Joan les Fonts.

The photo on the left is from the Route of Les Tres Colades, with its spectacular basalt cliffs. It shows the results of the cooling of the lava as it flowed towards the site of what is now Sant Joan les Fonts. On the right is a 12th-century Romanesque bridge in Besalú with a portcullis in center. It was partially destroyed during the Spanish Civil War, then rebuilt in the 60’s.

On the right is a 12th-century Romanesque bridge in Besalú with a portcullis in center. It was partially destroyed during the Spanish Civil War, then rebuilt in the 60’s. A view of Rupit and the nearby Salto de Sallent, a 100-meter waterfall. The photo below shows a cascade upstream from the main fall. There was an iron cross embedded in the rock, presumably marking the spot where someone had come too close to the edge. I decided not to go up closer to investigate. But it was impressive to see that the unpaved road crosses the stream above the main fall, going through six inches of water just a few feet from the 100-meter drop.

A view of Rupit and the nearby Salto de Sallent, a 100-meter waterfall. The photo below shows a cascade upstream from the main fall. There was an iron cross embedded in the rock, presumably marking the spot where someone had come too close to the edge. I decided not to go up closer to investigate. But it was impressive to see that the unpaved road crosses the stream above the main fall, going through six inches of water just a few feet from the 100-meter drop.

The idea was to build a home for the pigeons, a pigeonnier, where they could live comfortably and safely, and even be fed by the pigeon-lovers. This would preserve “the only sign of biodiversity in the city center.” In return, the pigeons would not mess the statues and they’d undergo population control. The money saved on cleaning statues would pay for the €40,000 construction and €9,000 annual maintenance.

The idea was to build a home for the pigeons, a pigeonnier, where they could live comfortably and safely, and even be fed by the pigeon-lovers. This would preserve “the only sign of biodiversity in the city center.” In return, the pigeons would not mess the statues and they’d undergo population control. The money saved on cleaning statues would pay for the €40,000 construction and €9,000 annual maintenance.