Sunrise out of the cabin

Ever since reading The Time Machine as a teenager, I, like most people, have wondered about time travel. And despite annoying naysaying from logicians and physicists, it still seems like an intriguing idea.

Susan and I just spent a week in far west Texas, where we experienced something like time travel. We stayed in a cabin in a caldera near Fort Davis. Other than a barbed wire fence, a single electric line, and a narrow, rutted dirt road there were no signs of human habitation––no other buildings, no cell service, no flights overhead.

An astute rancher might have pointed out that the male cattle were steers, not bulls, and that the cattle and many turkeys around were probably being raised for market. Closer inspection would reveal that there were some planted trees, both for shade and for pecans, but on the whole the impression was of desert isolation.

In this land the people are hard to find, but we could see yucca, sotol, ocotillo, prickly pear, sagebrush, mesquite, live oak, and uncountable wildflowers. We saw buzzards, mockingbirds, huge spiders, whitetail and mule deer. These living friends were framed by gorgeous sunrises and sunsets, and unbelievable cloud formations.

1854 Fort Davis (reconstructed)

This all made me think of my early days in Fort Worth. We lived then in the new suburbs on the edge of ranchland. In our childhood explorations we could find tarantulas and horned toads, tumbleweeds and cockleburs, scorpions and butterflies. The land seemed to stretch forever into remoteness and romance. When we looked up we could see the Milky Way and thousands of stars.

Fort Davis felt like that Fort Worth of long ago. The contentious Presidential race was irrelevant. The old cashier at the local market wanted to share interesting stories rather than to ring up grocery items. The buildings and houses looked like stage props for an old Western, until you realized that they were still in use, probably by the same family that settled here a century or two ago.

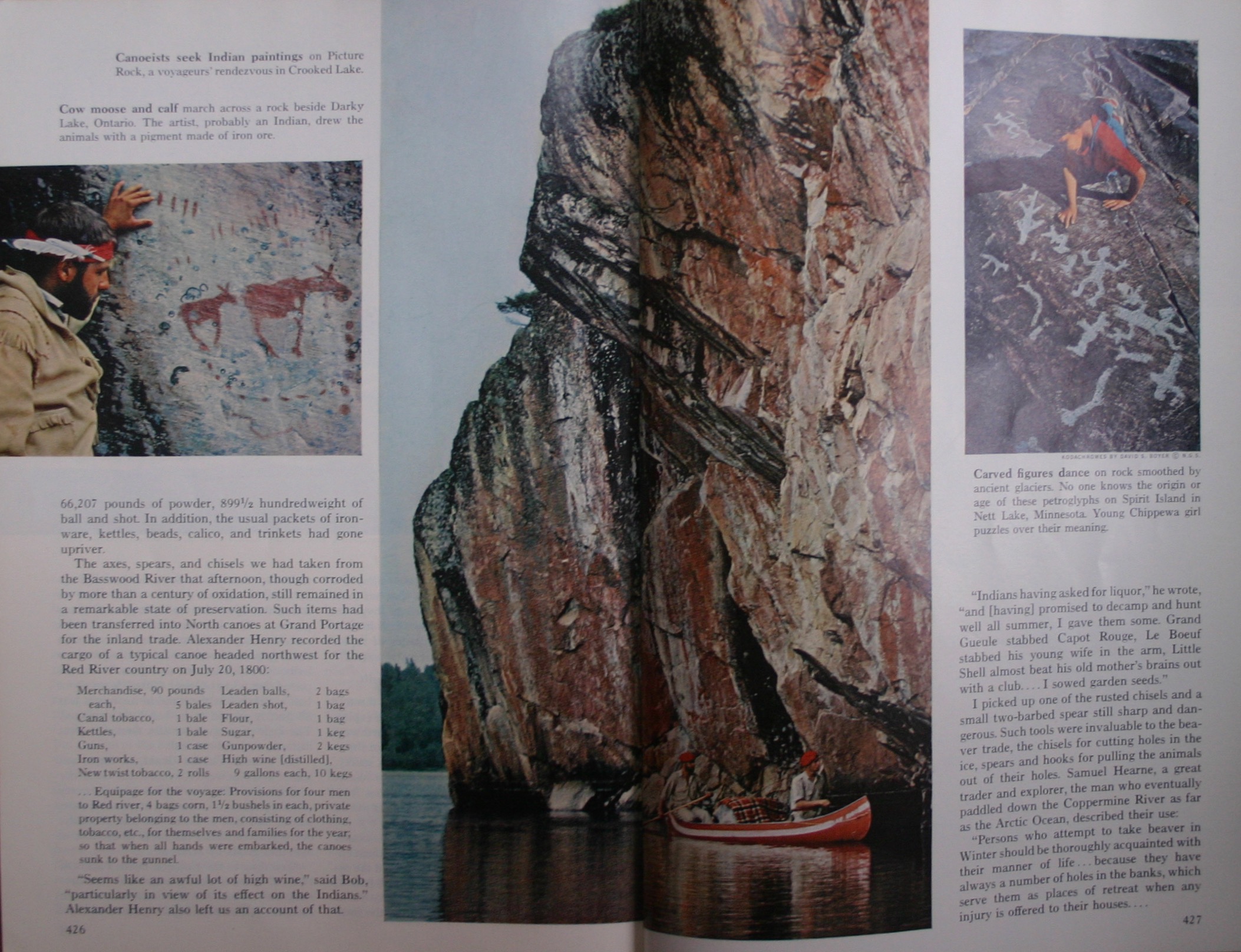

Rhyolite porphyry in fantastic shapes from volcanoes 35 million years ago

Fort Davis itself lies at the base of a rhyolite cliff, the south side of the caldera, or box canyon, that held our cabin. With just a few steps we could reach the path to climb the cliff shown above. Without realizing it, we zoomed even further back in time, to an era of intense volcanic activity, which created the Davis Mountains. The rhyolite columns, tuff and pumice, volcanic peaks and domes, took us entirely away from the human world.

The Hobby-Eberly Telescope at the UT McDonald Observatory (from mcdonaldobservatory.org)

But not long after that we learned what time travel could really be. We went to the nearby University of Texas McDonald Observatory, which takes advantage of the clear mountain air.

Among many projects at McDonald is the Hobby-Eberly Telescope Dark Energy Experiment (HETDEX). This seeks to uncover the secrets of dark energy, using the large Hobby-Eberly Telescope and to survey the sky 10x faster than other facilities can do. It will eventually create the largest map of the Universe ever, with over a million galaxies. In doing so, HETDEX will look back in time 10 billion years.

If there is anything more amazing than the mind-stretching that Fort Davis does, it is that the area is so little visited. In addition to the sites mentioned above, there is a state park with numerous hiking trails, the Chihuahuan Desert Nature Center and Botanical Gardens, interesting towns such as Alpine and Marfa, and the world’s largest spring-fed swimming pool, under the trees at Balmorhea State Park, which takes one back to the wonderful CCC projects of the 1930s.

Delbanco writes as a summer resident. As a full-time one, I can confirm what he says, and perhaps add a little texture. During the winter, the Transfer Center remains as the top attraction in town, the place where you see your friends and catch up on gossip. But it loses the bustle that Delbanco sees and definitely the stench.

Delbanco writes as a summer resident. As a full-time one, I can confirm what he says, and perhaps add a little texture. During the winter, the Transfer Center remains as the top attraction in town, the place where you see your friends and catch up on gossip. But it loses the bustle that Delbanco sees and definitely the stench. Wellfleet Transfer Center and Recycling Station) with our Forester filled to its gills, but often return with just as much stuff. That leaves me with mixed feelings. On the one hand there’s a sense of the great find, such as the canoe we retrieved, which only leaks a little. We typically come home with eight buckets of compost or mulch for the garden. The swap shop often has the perfect item that even Amazon can’t find.

Wellfleet Transfer Center and Recycling Station) with our Forester filled to its gills, but often return with just as much stuff. That leaves me with mixed feelings. On the one hand there’s a sense of the great find, such as the canoe we retrieved, which only leaks a little. We typically come home with eight buckets of compost or mulch for the garden. The swap shop often has the perfect item that even Amazon can’t find. Delbanco suggests that transferring and recycling trash is not so different from doing the same with words. He mentions E. E. Cummings in that regard, but may not realize a connection to Wellfleet.

Delbanco suggests that transferring and recycling trash is not so different from doing the same with words. He mentions E. E. Cummings in that regard, but may not realize a connection to Wellfleet.