After the earlier counterterrorism (CT) strategy failed in Afghanistan, the US began to emphasize counterinsurgency (COIN). Now that COIN has been shown to fail (e.g., as in WikiLeaks’s Afghan War Diary in ), we’re switching to CT again. This is called “evolving thinking.”

After the earlier counterterrorism (CT) strategy failed in Afghanistan, the US began to emphasize counterinsurgency (COIN). Now that COIN has been shown to fail (e.g., as in WikiLeaks’s Afghan War Diary in ), we’re switching to CT again. This is called “evolving thinking.”

When President Obama announced his new war plan for Afghanistan last year, the centerpiece of the strategy — and a big part of the rationale for sending 30,000 additional troops — was to safeguard the Afghan people, provide them with a competent government and win their allegiance.

Eight months later, that counterinsurgency strategy has shown little success, as demonstrated by the flagging military and civilian operations in Marja and Kandahar and the spread of Taliban influence in other areas of the country.

Our evolving thinking should be showing us that there is still no clearly articulated and shared goal for the US enterprise in Afghanistan. Without that, it’s difficult to say which of these two, or some other approach, does work or to recognize success once it’s achieved. As Andrew Bacevich writes (2010), there’s growing evidence that western way of war itself has failed.

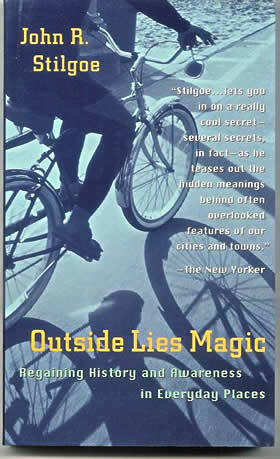

Harry Paget Flashman (see book cover above) had difficulty separating fiction from reality in his own exploits in Afghanistan. Apparently, reviewers of the Flashman books had the same problem. But we can’t afford to do that any longer in Afghanistan.

References

Bacevich, Andrew (2010, July 29). The end of (military) history? Mother Jones.

Cooper, Helene, & Landler, Mark (2010, July 31). Targeted killing is new U.S. focus in Afghanistan. The New York Times.

Kaplan, Fred (2009, March 24). CT or COIN? Obama must choose this week between two radically different Afghanistan policies. Slate.

Whitman, Alden (1969, July 29). Gen. Sir Harry Flashman and aide con the experts. The New York Times.

The

The

Gesa Kirsch recently pointed me to John R. Stilgoe’s, Outside lies magic: Regaining history and awareness in everyday places. It’s a refreshing call for becoming more aware of the ordinary world around us. Stilgoe urges us not only to walk or cycle more, but also to use the advantages of those modes of transport to see the world that we usually ignore.

Gesa Kirsch recently pointed me to John R. Stilgoe’s, Outside lies magic: Regaining history and awareness in everyday places. It’s a refreshing call for becoming more aware of the ordinary world around us. Stilgoe urges us not only to walk or cycle more, but also to use the advantages of those modes of transport to see the world that we usually ignore. The chapters—Beginnings, Lines, Mall, Strips, Interstate, Enclosures, Main Street, Stops, Endings—lie somewhere between prose poems, history lessons, and sermons about the everyday. They remind me of John McDermott’s summary that John Dewey “believed that ordinary experience is seeded with possibilities for surprises and possibilities for enhancement if we but allow it to bathe over us in its own terms” (1973/1981, p. x).

The chapters—Beginnings, Lines, Mall, Strips, Interstate, Enclosures, Main Street, Stops, Endings—lie somewhere between prose poems, history lessons, and sermons about the everyday. They remind me of John McDermott’s summary that John Dewey “believed that ordinary experience is seeded with possibilities for surprises and possibilities for enhancement if we but allow it to bathe over us in its own terms” (1973/1981, p. x). He shows the value of a camera, despite the lament that “ordinary American landscape strikes almost no one as photogenic” (p. 179). He recognizes the dread of causal photography (‘why are you photographing that vacant lot?’), but ties it to “deepening ignorance” (p. 181). This ignorance makes asking directions dangerous: People question us back, ‘Why do you want to know?’

He shows the value of a camera, despite the lament that “ordinary American landscape strikes almost no one as photogenic” (p. 179). He recognizes the dread of causal photography (‘why are you photographing that vacant lot?’), but ties it to “deepening ignorance” (p. 181). This ignorance makes asking directions dangerous: People question us back, ‘Why do you want to know?’

I was fortunate to have a visit with youth planners at the

I was fortunate to have a visit with youth planners at the  What I saw is part of

What I saw is part of  Sarah Van Wart from the UC Berkeley I School was my guide. She and two undergrads, Arturo and Sarir had been leading the high school students in a community planning exercise. They first examined their current situation, using dialogue, photos, and data. They then considered alternatives and how those might apply to a planned urban development project.

Sarah Van Wart from the UC Berkeley I School was my guide. She and two undergrads, Arturo and Sarir had been leading the high school students in a community planning exercise. They first examined their current situation, using dialogue, photos, and data. They then considered alternatives and how those might apply to a planned urban development project.  The development will include schools, housing, a park, and community center, but the questions for city planners, include “How should these be designed?” “How can they be connected?” “How can they be made safe, useful, and aesthetically pleasing?”

The development will include schools, housing, a park, and community center, but the questions for city planners, include “How should these be designed?” “How can they be connected?” “How can they be made safe, useful, and aesthetically pleasing?” On the day I visited, the youth had already developed general ideas on what they’d like to see in the development. Now they were to make these ideas more concrete through 3-D modeling. Using clay, toothpicks, construction paper, dried algae, stickers, variously colored small rocks, and other objects, they constructed scale models of the 30 square block development. One resource they had was contact sheets of photos of other urban environments. They could select from those to include as examples to emulate or to avoid.

On the day I visited, the youth had already developed general ideas on what they’d like to see in the development. Now they were to make these ideas more concrete through 3-D modeling. Using clay, toothpicks, construction paper, dried algae, stickers, variously colored small rocks, and other objects, they constructed scale models of the 30 square block development. One resource they had was contact sheets of photos of other urban environments. They could select from those to include as examples to emulate or to avoid. I was impressed with the dedication and skill of the leaders of the project, including also the teacher, Mr. G. But the most striking thing was how engaged the young people were. I heard some healthy arguing about design, but I didn’t see the disaffection that is so common some high schools today.

I was impressed with the dedication and skill of the leaders of the project, including also the teacher, Mr. G. But the most striking thing was how engaged the young people were. I heard some healthy arguing about design, but I didn’t see the disaffection that is so common some high schools today.  My only regret is that I wasn’t able to follow the process from beginning to end. But from the rich, albeit limited, glimpse I had, the project is an excellent way to engage young people in their own communities, to use multimedia for learning and action in the world, and to learn how to work together on meaningful tasks. It’s a good example of

My only regret is that I wasn’t able to follow the process from beginning to end. But from the rich, albeit limited, glimpse I had, the project is an excellent way to engage young people in their own communities, to use multimedia for learning and action in the world, and to learn how to work together on meaningful tasks. It’s a good example of