The Republic of Turkey was proclaimed on October 29, 1923. As its first President, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (photo below) sought to establish the modern Turkey as a “vital, free, independent, and lay republic in full membership of the circle of civilized states.” He recognized the need for “public culture,” which would enable citizens to participate fully in public life, and saw the unification and modernization of education as the key. Accordingly, one of his first acts was to invite John Dewey, who arrived in Turkey just nine months after the proclamation.

In this endeavor, the ideas of Atatürk and Dewey were consonant. Dewey’s words above (“vital, free, …”) could have been written by Atatürk, just as Dewey might have talked about “public culture.” Both recognized the need to institute compulsory primary education for both girls and boys, to promote literacy, to establish libraries and translate foreign literature into Turkish, and to connect formal schooling, the workplace, and government.

Today is John Dewey’s 149th birthday. Back in 1924, he was nearing the age of 65, when many people think of retiring. But his three-month-long study in Turkey was an ambitious project. He addressed issues of the overall educational program, the organization of the Ministry of Public Instruction, the training and treatment of teachers, the school system itself, health and hygiene, and school discipline. Within those broad topics, he studied and wrote about orphanages, libraries, museums, playgrounds, finances and land grants for education, and what we might call service learning or public engagement today.

He laid out specific ideas, such as how students in a malarial region might locate the breeding grounds of mosquitoes and drain pools of water of cover them with oil. In addition to learning science they would improve community health and teach community members about disease and health. Workplaces should offer day care centers and job training for youth. Libraries were to be more than places to collect books, but active agents in the community promoting literacy and distributing books. In these ways, every institution in society would foster learning and be connected to actual community life. As Dewey (1983, p. 293) argued,

The great weakness of almost all schools, a weakness not confined in any sense to Turkey, is the separation of school studies from the actual life of children and the conditions and opportunities of the environment. The school comes to be isolated and what is done there does not seem to the pupils to have anything to do with the real life around them, but to form a separate and artificial world.

Atatürk saw the need to unify Turkey into a nation state, despite its great diversity. Dewey supported that but emphasized that unity cannot come through top-down enforcement of sameness (p. 281):

While Turkey needs unity in its educational system, it must be remembered that there is a great difference between unity and uniformity, and that a mechanical system of uniformity may be harmful to real unity. The central Ministry should stand for unity, but against uniformity and in favor of diversity. Only by diversification of materials can schools be adapted to local conditions and needs and the interest of different localities be enlisted. Unity is primarily an intellectual matter, rather than an administrative and clerical one. It is to be attained by so equipping and staffing the central Ministry of Public Instruction that it will be the inspiration and leader, rather than dictator, of education in Turkey.

This was realized in many ways. For example, the central ministry should require nature study, so that all children have the opportunity to learn about and from their natural environment, but it should insist upon diversity in the topics, materials, and methods. Those would be adapted to local conditions, so that those in a coastal village might study fish and fishing while those in an urban center or a cotton-raising area would study their own particular conditions.

Many of Dewey’s ideas were implemented and can be seen in Turkey today, as we come upon its 85th birthday next week. What’s even more striking to me is how relevant they are to the US today. Many of our problems can be traced to the “separation of school studies from the actual life of children and the conditions and opportunities of the environment,” but also to the separation of work from learning, of health from community, of libraries from literacy development, or of universities from the public. Dewey would be the first to argue that we need to re-create solutions in new contexts, but his report from long ago and far away still provides insights for a way forward today.

References

Ata, Bahri (2000). The influence of an American educator (John Dewey) on the Turkish educational system. Turkish Yearbook of International Relations (Milletlerarası Münasebetler Türk Yıllığı), 31. Ankara: Ankara Üniversitesi.

Bilgi, Sabiha, & Özsoy, Seckin (2005). John Dewey’s travelings into the project of Turkish modernity. In Thomas S. Popkewitz (ed.), Inventing the modern self and John Dewey: Modernities and the traveling of pragmatism in education (pp. 153-177). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dewey, John (1983). Report and recommendations upon Turkish education. In Jo Ann Boydston (ed.), The Middle Works: Essays on Politics and Society, 1923-1924. Vol. 15 of Collected Works. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Press.

Wolf-Gazo, Ernest (1996). John Dewey in Turkey: An educational mission. Journal of American Studies of Turkey, 3, 15-42.

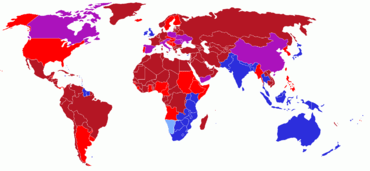

According to a new Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report, Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries, a combination of globalization, economic growth, and other societal changes has not only led to a larger gap between rich and poor nations; it’s also led to a growing gap between rich and poor in more than three-quarters of OECD countries over the past two decades.

According to a new Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report, Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries, a combination of globalization, economic growth, and other societal changes has not only led to a larger gap between rich and poor nations; it’s also led to a growing gap between rich and poor in more than three-quarters of OECD countries over the past two decades.