As we’re about to set off on a trip both to explore and to discuss progressive education, I’m thinking about the example of the Misiones Pedagógicas in Spain in the early 1930’s.

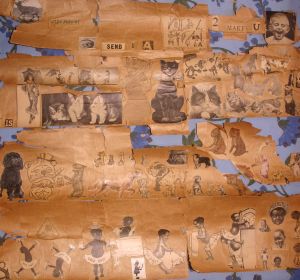

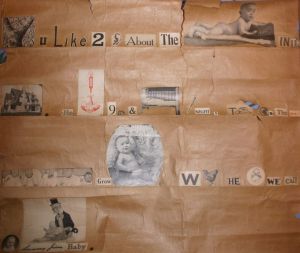

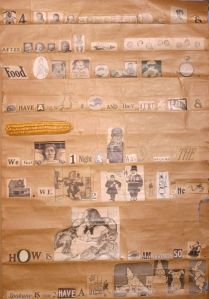

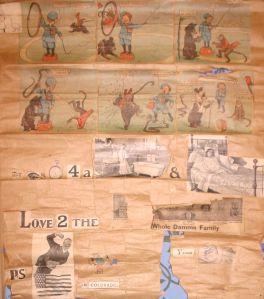

My colleague, Iván M. Jorrín Abellán, just sent a link to a digital copy of the 1934 report: Patronato de Misiones Pedagógicas : septiembre de 1931-diciembre de 1933, in the collection of the Bibliotecas de Castilla y León. It tells the story of the Misiones through text, photos, and a map. Even if your Spanish is as poor as mine you can enjoy the many photos and get enough of the text to appreciate the project.

Some of the photos of uplifted, smiling faces are a bit much for today’s cynical eyes. Still, it’s hard to deny that something important was happening for both the villagers and the missionaries.

The Misiones Pedagógicas were a project of cultural solidarity sponsored by the government of the Second Spanish Republic, created in 1931 and dismantled by Franco at the end of the civil war. Led by Manuel Bartolomé Cossio, the Misiones included over five hundred volunteers from diverse backgrounds: teachers, artists, students, and intellectuals. A former educational missionary, Carmen Caamaño, said in an interview in 2007:

We were so far removed from their world that it was as if we came from another galaxy, from places that they could not even imagine existed, not to mention how we dressed or what we ate, or how we talked. We were different. –quoted in Roith (2011)

The Misiones eventually reached about 7,000 towns and villages. They established 5,522 libraries comprising more than 600,000 books. There were hundreds of performances of theatre and choir and exhibitions of painting through the traveling village museum.

We are a traveling school that wants to go from town to town. But a school where there are no books of registry, where you do not learn in tears, where there will be no one on his knees as formerly. Because the government of the Republic sent to us, we have been told we come first and foremost to the villages, the poorest, the most hidden and abandoned, and we come to show you something, something you do not know for always being so alone and so far from where others learn, and because no one has yet come to show it to you, but we come also, and first, to have fun. –Manuel Bartolomé Cossio, December 1931

There’s an excellent documentary on the Misiones, with English subtitles. It conveys simultaneously the grand vision and the naïveté, the successes and the failures. As Caamaño says, “something unbelievable arrived” [but] “it lasted for such a short time.”

In her study of Spanish visual culture from 1929 to 1939, Jordana Mendelson (2005) examines documentary films and other re-mediations of materials from the Misiones experience. Her archival research offers a fascinating contemporary perspective on the cultural politics of that turbulent decade, including the intersections between avant-garde artists and government institutions, rural and urban, fine art and mass culture, politics and art.

I’m struck by several thoughts as I view the documentation on the Misiones. Today’s Spain is more literate, more urban, more “modern”. But although the economic stresses are different, they have not disappeared. There are still challenges, in some ways greater, for achieving economic and educational justice.

Iván and other educators are asking how the spirit of the Misiones might influence community-based pedagogy in current times. Their experiences have lessons for those outside of Spain as well.

References

Acacia Films (2011). Misiones Pedagógicas 1934 – 1936. República española.

Board of Educational Missions (1934). Patronato de Misiones Pedagógicas : septiembre de 1931-diciembre de 1933. Madrid.

Mendelson, Jordana (2005). Documenting Spain: Artists, exhibition culture, and the modern nation, 1929–1939. State College: Penn State University Press.

Roith, Christian (2011).High culture for the underprivileged: The educational missions in the Spanish Second Republic 1931 – 1936. In Claudia Gerdenitsch & Johanna Hopfner, (eds.), Erziehung und bildung in ländlichen regionen–Rural education (pp. 179-200). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.