Last Monday night, we visited Square Louise Michel at the foot of Sacre Coeur in Paris. The park and the nearby streets of Montmartre are a living history book, with every cobblestone suggesting times of struggle, hope, fear, and disillusionment. Staying there for a few days makes me feel that I just have to share some thoughts about the Paris Commune and Louise Michel.

Last Monday night, we visited Square Louise Michel at the foot of Sacre Coeur in Paris. The park and the nearby streets of Montmartre are a living history book, with every cobblestone suggesting times of struggle, hope, fear, and disillusionment. Staying there for a few days makes me feel that I just have to share some thoughts about the Paris Commune and Louise Michel.

There was a time when I knew very little about the Paris Commune, which held Paris for two months in the spring of 1871. It wasn’t part of my history lessons in school, nor did it enter into political debates or everyday conversations. As I read, I began to see references to it—”the democratic and social republic!”, the petroleuses, the horrible siege prior to the commune, which led to the eating of zoo animals, the Federales’ Wall, early establishment of rights for women, why Sacre Coeur was built—but these references were disjointed, so that much what I did know was confused and contradictory. It took living in Paris for a year to help me understand more of what it was about.

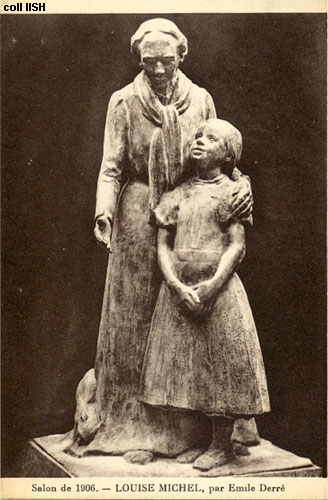

I knew even less about Louise Michel, one of the heroes of the Paris Commune, and as I’m learning, much more besides. But I feel a shiver now whenever I think of her. I’m amazed by her passion and ideals, the violence in her life, her writing, her work as an educator in many senses of that word, and her life fully lived.

For a long time Michel was the only woman other than saints to have a Paris métro named after her. The recent renaming of the Pierre Curie métro to Pierre et Marie Curie makes two (or one and a half). Schools all over France bear her name as well. She comes alive in books such as

For a long time Michel was the only woman other than saints to have a Paris métro named after her. The recent renaming of the Pierre Curie métro to Pierre et Marie Curie makes two (or one and a half). Schools all over France bear her name as well. She comes alive in books such as Édith Thomas’s The Women Incendiaries (reprinted by Haymarket Books, 2007; original in French in 1963). I think of her when I play Le Temps des Cerises, a song often associated with the commune and with Michel, even though it was written five years before the Commune.

I’ve also learned that she was an early practitioner of what I’d call inquiry-based teaching and learning. She was a continual learner, inspired by the works of Charles Darwin and Claude Bernard. As a school teacher, she used methods promoted in the progressive education movement (which came much later): interaction with objects such as flowers, rocks, and animals, studies outdoors, and scientific methods. She declared,

The morality I was teaching was this: to develop a conscience so great that there could exist no reward or punishment apart from the feeling of having done one’s duty, or having acted badly.

After the Commune fell, Michel was deported to New Caledonia. Unlike her jailers and many of the other Communards, she befriended Polynesians. She gave lessons to one in “the things whites know,” while he taught her his language. Later, she ventured deep into the forest to work with and study groups still practicing cannibalism. She collected their legends and music as a modern ethnographer might do. When there was a native revolt, Michel joined the side of the Polynesians. Throughout, she wrote poetry, prose, and letters on behalf of prisoner rights.

Later, she opened a school in London for the children of political refugees (The International School). There was a statement in the prospectus taken from Mikhail Bakunin’s God and the State:

All rational education is at bottom nothing but this progressive immolation of authority for the benefit of liberty, the final object of education necessarily being the formation of free men full of respect, and love for the liberty of others.

As infed says, there were no compulsory subjects, teaching was in small groups, and there was an emphasis on rational and integral education. Often, groups of children would bring their own ideas about what to study. Michel wanted students to learn to think for themselves, just as she did herself and encouraged others to do throughout her life.

Louise Michel was a complex person whose every year might fill the life for someone else; a blog post feels totally inadequate. Moreover, one might criticize both the Commune and her participation on many grounds. Nevertheless, her commitment to social justice, her caring for all life, her passion for learning and teaching, her striving for women’s rights and democracy in general, her unselfish work on behalf of others, her strong moral stance, and her unfailing courage set a mark to inspire anyone.

References

- Michel, Louise (2004). Louise Michel [Rebel lives series, Nic Maclellan, ed.). New York: Ocean.

- Saudrais, Hélène (2005). Louise Michel. Amsterdam: International Institute of Social History.

- Thomas, Édith (2007/1963). The women incendiaries. Chicago: Haymarket Books (reprinted in 2007; original in French, Les Petroleuses, in 1963).

Visited Paris this week and saw the square named after Louise Michel in front of the Cathedral. As a historian, I almost fell over in shock. What a nasty joke modern Socialists have played on the Church! After all, the Sacre Coeur was built as a response to the Commune – and not a positive one. Also, as a good Anarchist, Louise Michel would have had a dim view of the Church. Sadly, when I mentioned the square needed a statue of Louise Michel giving the Sacre Coeur the middle finger salute, the joke was lost on both the tourists and the French. I don’t agree with all her politics, but I understand the context in which she promulgated them. She was a fiery woman who, according to historian Aleister Horne, demanded the Communards follow up their seizing Paris by crushing the militarily weak national government immediately. If the Communards had taken her advice they would have won as the government had scarcely a company of timid Soldiers at their disposal.

LikeLike