In my last post I talked about the Eight-Year-Study, which documented the success of progressive education at fostering intellectual curiosity, cultural awareness, practical skills, a philosophy of life, a strong moral character, emotional balance, social fitness, sensitivity to social problems, and physical fitness.

I had come across materials related to the study in the Progressive Education Association Records in the University of Illinois Archives. This is a treasure-trove, not only of the Progressive Education Association per se, but also of the various social movements they were involved in. I hope to explore it more.

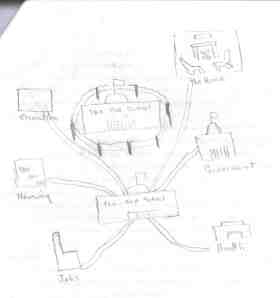

One drawing I found is shown here. It’s included in the folder for the booklet that later appeared as Dare our secondary schools face the atomic age? However, there are no images in that booklet. The drawing shows two visions for schools. In one, the “old school,” there is a fence surrounding the building; activities of the school are separate from those of the world around it, and as a result, schooling is separated from the actual life of the children.

In a second vision, the “new school,” the building is substantially the same, but it is connected to sites for recreation, housing, jobs, health, government, and by implication, all aspects of life. This idea of community-based schools was key to the Progressive Education movement, especially in its later years, as members realized they needed to do more than promote child-centered learning in an individual sense. That was true for “community schools” per se (Clapp, 1939), but actually for all schools, urban or rural, large or small, primary or secondary.

Today, many of these ideas have survived under rubrics such as “civic engagement,” “public engagement,” “community-based learning,” or “service learning.” But often those ideas are seen as one-way or very limited in scope, as in a single course. It’s worth revisiting the earlier visions to understand better how schools and universities could better fulfill the high hopes we place upon them.

References

Benedict, Agnes E. (1947). Dare our secondary schools face the atomic age?. New York: Hinds, Hayden & Eldredge.

Benedict, Agnes E. (1947). Pencil drawing, Progressive Education Association Records, 1924-1961, Record Series 10/6/20, Box 4, folder Dare the Schools Face the Atomic Age?, University of Illinois Archives.

Clapp, Elsie Ripley (1939). Community schools in action. New York: Viking.