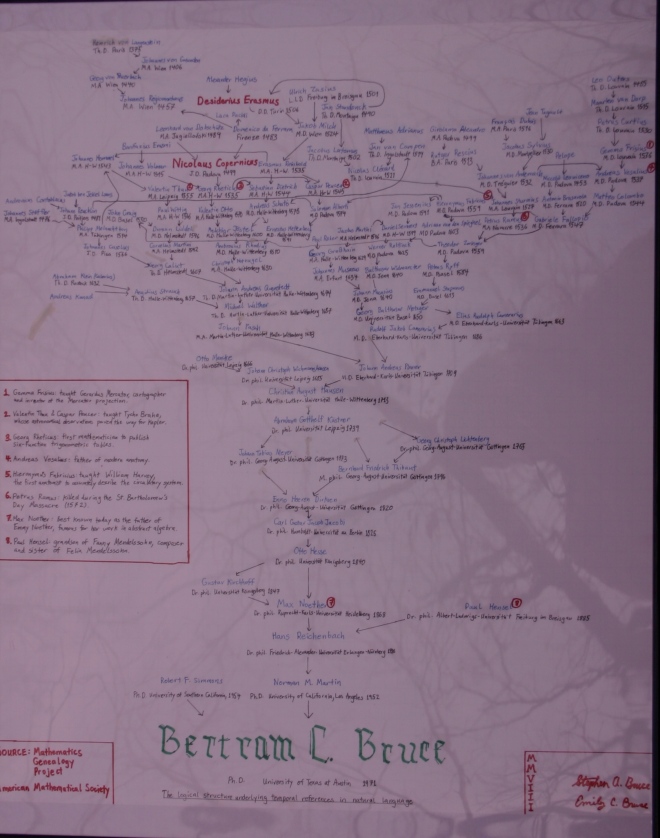

My academic career includes degrees in biology and computer science, teaching computer science in two universities, research in a high-tech, R&D firm, teaching in a college of education, and teaching now in a school of library and information science. My dissertation adviser was in philosophy, and the dissertation itself was in mathematical logic and artificial intelligence. I’ve published in a variety of journals, including those in other fields. People have often asked: Is there any rationale for this? Were you just booted from one place to another?

I could give a practical account of why I moved to a library and information science school nine years ago, but that wouldn’t explain how I think of the field and what led me to that decision. To do that, I need to start a bit earlier…

Chip in Fort Worth, 1954

When I was three years old, I enrolled along with four other children in the

Frisky and Blossom Club held at the Fort Worth Children’s Museum (now the

Fort Worth Museum of Science and History). Frisky and Blossom were de-scented skunks who lived in the old house that was the Museum then. The club evolved into the Museum School, the largest in the US, with over 200,000 alums. I stayed with the school, learning about plants and animals, astronomy, history, and many other topics. Most importantly, I learned how energizing learning could be when it’s connected to what we care about and how it can grow out of things in the world around us.

That interest in informal learning bolstered by museums and libraries, continued. When I was eight years old, I never missed the bookmobile when it came by our neighborhood. I was a collector of insects, sea shells, postage stamps, books, and all sorts of other things. But reading and writing were the most important means for expanding my world. It’s sad to say, but little of this occurred for me in school, which often felt like some unjustified punishment. I learned arithmetic from card and board games outside of school, but also by counting the minutes until the end of the class, the school day, or the school year. Science was as much through a chemistry set and nature study as through classes. And so on.

These experiences led me to value

inquiry-based learning. They also made it harder for me to understand knowledge as confined within static categories. When I applied to college, I considered majoring in history, geology, biology, and English, but later thought philosophy or behavioral sciences might be better. For graduate school, I chose computer sciences, not because I was so enamored of the machine, but because the field appeared the be the closest to offering a general tool for interdisciplinary inquiry. My work in artificial intelligence emphasized computer natural language understanding and reasoning. That led in a more direct way than might appear at first into education. Fortunately, working on projects such as a statistics curriculum and software for high school students, or

Quill, a program for reading and writing, allowed me to create learning environments that were more integrated and connected to the life of students, something I had missed to a large extent in my own schooling.

Later, I brought those experiences to a college of education. I found many opportunities to expand on those experiences. But I also found that the means of formal schooling were sometimes disconnected from the ends I valued. The emphases on measurable learning objectives and teacher credentialing often crowded out discourse on the changing nature of literacy or the connection of learning and life. Because my work involves collaborations with those in other disciplines, I saw space for those ideas in other realms, such as writing studies, communication, occasionally in the sciences, and especially, in library and information science.

Chip in Dublin, 2007

As I worked with people in library and information science, I found a serious engagement with issues such as the moral and political aspects of texts and information systems, changes to literacy practices related to new technologies and globalization, distributed knowledge making, information for community needs, and new ways of organizing and providing access to information. Although not all of my colleagues would characterize it this way, I see issues of learning threaded through everything we do. Learning is the creative act of meaning making that occurs in praxis, the integration of theory and practice. More than any other discipline, library and information science provides the space to engage with that phenomenon. It brings together the informed and critical understanding of texts and information systems with serious attention to the impact on human life.

There are many other reasons I might add for my joining GSLIS per se–the high level of collegiality, the moral commitment, the respect for both the old and the new, and the sincere interest in and openness to continuing to learn. These things make coming to library and information science seem wise, in spite of myself and my meandering path.

Several years ago, I read Schopenhauer’s porcupines: Dilemmas of intimacy and the talking cure: Five stories of psychotherapy, by Deborah Anna Luepnitz.

Several years ago, I read Schopenhauer’s porcupines: Dilemmas of intimacy and the talking cure: Five stories of psychotherapy, by Deborah Anna Luepnitz. Schopenhauer presents his parables as telling us just how life is, but Luepnitz takes this one in a constructive way. She shows through five case studies how we all have simultaneous needs and fears for intimacy, thus creating a dilemma for full living. As she puts it (p. 19):

Schopenhauer presents his parables as telling us just how life is, but Luepnitz takes this one in a constructive way. She shows through five case studies how we all have simultaneous needs and fears for intimacy, thus creating a dilemma for full living. As she puts it (p. 19):