This video about Youth Community Informatics is already on the YCI site, but some readers may not have seen it there. It gives the flavor of the project; for more details, please visit the site.

democracy

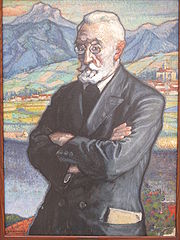

John Dewey and Daisaku Ikeda

I attended the 6th Annual Ikeda Forum for Intercultural Dialogue yesterday at the Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue in Cambridge. The topic was John Dewey, Daisaku Ikeda, and the Quest for a New Humanism. The occasion was the 150th Anniversary of John Dewey’s birth.

I attended the 6th Annual Ikeda Forum for Intercultural Dialogue yesterday at the Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue in Cambridge. The topic was John Dewey, Daisaku Ikeda, and the Quest for a New Humanism. The occasion was the 150th Anniversary of John Dewey’s birth.

Although Ikeda’s Nichiren Buddhism, a form of Mahayana Buddhism, may at first seem far removed from Dewey’s American pragmatism, the speakers found many areas of consonance between the work of the two. I was pleased to see that Jane Addams was brought into the conversation, too.

Nichiren was a 13th century Buddhist reformer, who based his teachings on the Lotus Sutra and its message of the dignity of all life. Like Dewey’s pragmatism, Nichiren Buddhism is grounded in the realities of daily life. It promotes “human revolution,” in which individuals take responsibility for their lives and help to build a world in which diverse peoples can live in peace.

Nichiren was a 13th century Buddhist reformer, who based his teachings on the Lotus Sutra and its message of the dignity of all life. Like Dewey’s pragmatism, Nichiren Buddhism is grounded in the realities of daily life. It promotes “human revolution,” in which individuals take responsibility for their lives and help to build a world in which diverse peoples can live in peace.

Ikeda is the founder of the Soka Gakkai International, a movement characterized by its emphasis on value creation (soka). This implies that each individual needs the opportunity to find value in their unique path while contributing value to humanity. Soka schools have much in common with the kinds of schools Dewey envisaged (but rarely saw enacted).

At the Ikeda Forum discussions focused on connections and divergences between Dewey’s naturalistic humanism and Ikeda’s Buddhist humanism. Presentations examined how their work can be used as resources for individual and social change.

How useful is the concept of community?

Miguel de Unamuno says that anyone who invents a concept takes leave of reality. I like that statement both for its literal meaning that reality can nver be fully captured by a single concept, and in the suggestion that concepts imply a kind of madness.

Miguel de Unamuno says that anyone who invents a concept takes leave of reality. I like that statement both for its literal meaning that reality can nver be fully captured by a single concept, and in the suggestion that concepts imply a kind of madness.

Unamuno’s dictum applies to the question “How useful is the concept of community?”, because community designations betray the individual in two senses. One is that every community designation necessarily strips away the uniqueness of the individuals within. A term such as “immigrants” is clearly impoverished with respect to the many reasons, origins, and experiences of immigrants.

But a community designation can not only strip away individual meaning; it can attach wrong, or even contradictory meanings. For example, if we say that someone is a member of the “elderly community,” we impute a large set of attributes that may be totally off. She might be 90 years old, but rather than suffering “elderly decline,” she might be longing for that iPod we had provided to the “youth community” to share the latest music. There’s even some evidence that the very old are healthier than the somewhat old, because they were the ones who survived past critical health hurdles.

What makes this all even more interesting is that we can’t think without concepts, and we do better when we make use of even faulty information. A member of the “library patron community” may come to the library to get warm, to order some coffee (as at Urbana Free Library), to get a date, to sleep, or a host of other reasons.

Nevertheless, it’s helpful to know that many visitors seek information. Similarly, many immigrants may need help dealing with often absurd regulations that don’t apply to citizens in a country. Many elderly people have special physical or mental challenges well beyond those faced by most younger people.

These thoughts keep bringing me back to the need for dialogue. In so many cases, well-intentioned people make judgments and decisions without really listening to those they’re trying to help. Most examples of community designations betraying the individual, could at least be better addressed by starting with the idea of listening to each others’ experiences first.

References

- De Unamuno, Miguel (1921). Del sentimiento trágico de la vida (The tragic sense of life). New York: Macmillan.

White privilege

Peggy McIntosh’s essay, White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack” (1990) provides a very accessible discussion of race/racism, in particular, how whites have trouble even seeing it. She identifies 50 daily effects of white privilege, “conditions that…attach somewhat more to skin-color privilege than to class, religion, ethnic status, or geographic location” per se.

McIntosh predicts that if you’re White you’ll answer “yes'” to most of these, and if you’re Black, you’ll say “no” to many of them. Try it yourself. For example,

1. I can if I wish arrange to be in the company of people of my race most of the time.

6. I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.

7. When I am told about our national heritage or about “civilization,” I am shown that people of my color made it what it is.

21. I am never asked to speak for all the people of my racial group.

22. I can remain oblivious of the language and customs of persons of color who constitute the world’s majority without feeling in my culture any penalty for such oblivion.

24. I can be pretty sure that if I ask to talk to the “person in charge”, I will be facing a person of my race.

25. If a traffic cop pulls me over or if the IRS audits my tax return, I can be sure I haven’t been singled out because of my race.

34. I can worry about racism without being seen as self-interested or self-seeking.

44. I can easily find academic courses and institutions which give attention only to people of my race.

John Berry (2004) adapts these for the library profession. I like both of these articles, and can imagine ways to use such lists to spark a discussion.

I would have to answer yes to most of the statements myself. Then I imagined it for my time in Ireland (thinking more about nationality, than about race per se). Still mostly yes, but some no’s and some harder to answer. When I thought about my stay in Turkey, there were fewer yes’s. For Haiti, fewer still.

But what was most interesting to me is that even for Haiti, I could still say yes to most of the statements, even though I’m the outsider there in terms of race, nationality, language, culture, and above all, economic class. The fact that I can take myself mentally to Haiti, and still possess White Privilege shows even more to me why it’s such a powerful social construct. It also reveals why it’s so hard to understand and accept that one possesses that unfair privilege.

In a Harvard Law Review article, Cheryl Harris (1993), takes this concept further, arguing that racial identity and property are deeply intertwined. She examines “how whiteness, initially constructed as a form of racial identity, evolved into a form of property, historically and presently acknowledged and protected in American law.”

References

- Berry, John D. (2004, June 15). BackTalk: White privilege in library land. Library Journal.

- Harris, Cheryl I. (1993, June). Whiteness as property. Harvard Law Review, 106(8), 1707-1791.

- McIntosh, Peggy (1990, Winter). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack”. Independent School.

The Soloist (2009)

The Soloist (2009) is an excellent film based on the true-life book, The Soloist by Steve Lopez. Lopez is a Los Angeles Times columnist who discovers Nathaniel Ayers, a Juilliard School dropout, who becomes schizophrenic and homeless, living on the streets of LA.

Ayers is a classically-trained cellist, who now has only a two string violin to play and instead of a concert stage, an urban tunnel or street corner. Lopez wonders how Ayers can stand to play in those conditions, but Ayers tells him that “the only thing that I hear is the music and the applause of the doves and the pigeons.” Ayers is hooked and decides to write a series of feature articles in the Times.

Robert Downey Jr. portrays Lopez in the movie, and Jamie Foxx portrays Ayers. The two main characters give terrific performances, as do the actual homeless extras from the Lamp Community.

Ayers’s story makes us wonder about the many other homeless people in LA and elsewhere. As Lamp says,

Close to 74,000 people are homeless in Los Angeles–more than in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco combined. Los Angeles’ Skid Row, a 52-block area east of the downtown business district, has the highest concentration of homelessness in the United States. More than half of the homeless men and women in this area are chronically homeless, meaning they struggle with a mental or physical disability and have been living on the street for years.

That relatively greater challenge in LA doesn’t of course diminish the shameful job we do across the US in dealing with homelessness. The book, Ayers’s music, and the movie all reinforce Jane Addams’s view that art and cultural activities can reduce our isolation form one another, and reinforce essential human: “Social Life and art have always seemed to go best at Hull-House.”

The DVD includes features with the real Steve Lopez and Nathaniel Ayers, and also, Beth’s Story, an animated short telling another story of homelessness:

References

Addams, Jane (1930). The second twenty years at Hull-House: September 1909 to September 1929. New York, Macmillan.

Health care illogic

Following Rep. Joe Willon’s (R, SC) outburst druing the President’s speech, the Obama administration has scrambled to show that it will guarantee no reasonable means of healthcare for people in the US illegally. That position strikes many people as sensible. But it’s not only cruel, unfair, and unmanageable, it actually undermines the very effort to secure affordable, reliable healthcare for everyone.

No one in power is even talking about government health care for all (that’s a plan that would really work). Instead, the proposal is simply to require everyone to get health care insurance, through a government-managed insurance exchange, employer-provided group coverage, or private insurance. With a large pool of buyers in the exchange, it’s possible that health care costs could be controlled.

Denying undocumented workers and their families access to both the exchange and employer-provided group coverage means that very few will have insurance of any kind. This, in turn, will increase demands on expensive emergency room care, whose costs are ultimately borne by the government and individuals with private insurance.

Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D, IL) put it this way last week:

So, and remember, we’re not talking about government health care, we’re talking about everybody is going to be required to get health care insurance,” said Gutierrez. “And so as we go to this big store, right, where everybody is required. And this exchange, the health care exchange, where if you don’t have health care you are required to go purchase it. When you go and attempt to purchase it, what does the administration say? The administration says, ‘You will have to prove that you are legally in the United States and have a Social Security number and a right to that.’

Some immigrants, and let me say it – hundreds of thousands of them — who have businesses, who are prospering, who are paying taxes— even when they wish to buy because it’s going to be a requirement to buy it, this administration has told them don’t buy. You can’t. You can’t buy.

One thing that could make the exchange work is to bring in large numbers of relatively healthy people. New immigrants use 55% less health care than native-born Americans, according to a Harvard/Columbia University study (Physicians for a National Health Program, 2005).

Denying health insurance is foolish and spiteful. It’s also absurd: We should demand that immigrants share the burden of paying for healthcare, not exclude them in a way that ultimately endangers not only theirs, but everyone’s health and finances.

See also The bottom line in health care.

References

Physicians for a National Health Program (2005, July 27). Immigrants’ health care costs are low.

What do Boston & Cambridge have to say to Champaign Unit 4?

Ann Abbott inspired me to say more about the connections between the Boston desegregation experience in my last post and that of Champaign Unit 4.

Ann Abbott inspired me to say more about the connections between the Boston desegregation experience in my last post and that of Champaign Unit 4.

I’d have to say that Boston is a good example of how not to do it. As I said in that post, Judge Garrity made the correct, and only legally justifiable decision, but rulings alone cannot accomplish much if there is widespread resistance, especially from political and religious leaders, school officials, and media. The racism thwarted integration of the schools, and in the process did major damage to the school system and to Boston as a civilized city.

In contrast, just across the Charles River, Cambridge managed relatively successful desegregation during the same period. Cambridge adopted a “freedom of choice” or “controlled open enrollment” desegregation plan in 1981. Parents would specify a list of the schools they wanted their children to attend. Their preferences were followed as long as explicit desegregation controls could be maintained. There were no guarantees of attending any particular school.

Because the program was coupled with interesting magnet programs at every school, there were many viable options for families. As parents we almost welcomed the fact that we didn’t have to make the final choice between the Maynard School’s dual language (two-way Spanish-English bilingual) program, Tobin’s School of the Future, with innovative uses new technologies, the Graham & Parks Alternative Public School, with its open education plan (see mural above), or the closer by Peabody, Fitzgerald, or Lincoln schools, each with things to recommend it. It helped that Cambridge did not have the urban sprawl of midwestern cities, which meant that unlike Champaign, Cambridge offered several schools within walking distance.

Because the program was coupled with interesting magnet programs at every school, there were many viable options for families. As parents we almost welcomed the fact that we didn’t have to make the final choice between the Maynard School’s dual language (two-way Spanish-English bilingual) program, Tobin’s School of the Future, with innovative uses new technologies, the Graham & Parks Alternative Public School, with its open education plan (see mural above), or the closer by Peabody, Fitzgerald, or Lincoln schools, each with things to recommend it. It helped that Cambridge did not have the urban sprawl of midwestern cities, which meant that unlike Champaign, Cambridge offered several schools within walking distance.

Although not without its problems, this plan was effective in substantially desegregating Cambridge schools, and maintained public support and involvement with the public schools. It’s not surprising then that Robert Peterkin, Superintendent, was called in as a consultant on the similar plan in Champaign. The story in Champaign is still unfolding (as it is in Cambridge and Boston as well). But if I had to draw lessons today from these three experiences, I’d say that it’s essential for Champaign residents today to avoid the disastrous path of resistance that Boston experienced

The Champaign school district has been struggling to address concerns such as too many black students in special education and discipline referrals; too few in gifted and honors classes; and black students being bused out of their neighborhoods. Responses such as denying the problems or siting new schools outside of black communities (though still technically north side) remind me of Boston’s response. Everyone would benefit if the school system and residents were to embrace not only the technical details of the Cambridge (or similar) plan, but also the spirit that saw how desegregation could enrich the learning for all.

The Champaign school district has been struggling to address concerns such as too many black students in special education and discipline referrals; too few in gifted and honors classes; and black students being bused out of their neighborhoods. Responses such as denying the problems or siting new schools outside of black communities (though still technically north side) remind me of Boston’s response. Everyone would benefit if the school system and residents were to embrace not only the technical details of the Cambridge (or similar) plan, but also the spirit that saw how desegregation could enrich the learning for all.

References

- Alves, Michael J. (1984). Cambridge desegregation succeeding. Equity & Excellence in Education, (1), 178 – 187. (Eric# ED251520)

- Heckel, Jodi (2009, September 16). Focus of hearing on Champaign consent decree: Trust. The News-Gazette.

Don’t blame Judge Garrity for the failure of school busing in Boston

W. Arthur Garrity Jr., the federal judge whose order to desegregate Boston’s public schools triggered mob violence and an image of bigotry in the city that prided itself on being the cradle of American liberty, died Thursday of cancer.

Garrity’s death at 79 came two months after the Boston school board voted to end busing for integration, 25 years after Garrity’s order launched a tumultuous period in the city’s history.

via W. A. Garrity; Judge Desegregated Boston Schools – Los Angeles Times.

I moved to the Boston area on the first of June, 1974. On June 21, Judge Garrity filed a 152-page opinion, in which he ruled that the School Committee of the city of Boston had “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting all of the city’s students, teachers and school facilities.” The ruling was unanimously affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals. It ordered the School Committee to desegregate Boston schools by instituting student assignment, teacher employment, and facility improvement procedures, as well as the use of busing on a citywide basis. When the Committee failed to present an adequate plan the court assumed an active role in in the desegregation, a role that continued for fifteen years, my entire time of living in the Boston area.

I moved to the Boston area on the first of June, 1974. On June 21, Judge Garrity filed a 152-page opinion, in which he ruled that the School Committee of the city of Boston had “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting all of the city’s students, teachers and school facilities.” The ruling was unanimously affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals. It ordered the School Committee to desegregate Boston schools by instituting student assignment, teacher employment, and facility improvement procedures, as well as the use of busing on a citywide basis. When the Committee failed to present an adequate plan the court assumed an active role in in the desegregation, a role that continued for fifteen years, my entire time of living in the Boston area.

The Community Action Committee of Paperback Booksmith, a bookstore in the area, published the decision in 1974 as The Boston School Decision. Publishing a lengthy court opinion may seem like a foolish business decision, but it was in fact a courageous and consequential act to inform the public debate. I still have my well-read copy.

Following the decision, there was resistance, violence, and white flight. When regular drivers refused to drive buses for schoolchildren out of racism or fear for their own safety, brave people, such as my friend Henry Kingsbury, volunteered to take their place. Given all that and the fact that 30 years later, the Boston schools had become even more segregated than before, one might consider Judge Garrity’s decision to be a failure. A persistent myth arose that this was an example of social engineering gone awry. For example, Bruce G. Kauffmann, in “Judge took Beantown for bumpy ride in 1974” describes it as “a liberal judge’s infatuation with experimental social engineering programs.”

But Garrity was both courageous and correct. The problem was not his, nor anyone else’s, attempt to engineer social relations. For twenty years after the Supreme Court had ruled that the legal maintenance of segregated schools violated the US Constitution, and even more, the fundamental values of the United States for simple justice, the Boston School Committee and other political leaders steadfastly resisted every attempt at incremental reforms. Ideas about placement of schools, magnet programs, voluntary busing, and so on, which might have led to gradual and peaceful integration, were subverted or outright blocked.

But Garrity was both courageous and correct. The problem was not his, nor anyone else’s, attempt to engineer social relations. For twenty years after the Supreme Court had ruled that the legal maintenance of segregated schools violated the US Constitution, and even more, the fundamental values of the United States for simple justice, the Boston School Committee and other political leaders steadfastly resisted every attempt at incremental reforms. Ideas about placement of schools, magnet programs, voluntary busing, and so on, which might have led to gradual and peaceful integration, were subverted or outright blocked.

The decision demonstrates conclusively that the School Committee had consistently and deliberately acted to thwart Constitutional guarantees of equal rights, not only maintaining the “separate” aspect of Jim Crow, but failing also at any semblance of the “equal.” Schools designated for Black children were not just segregated, but denied resources in terms of teacher preparation, class size, curriculum, materials, physical plants, and other necessary tools for learning.

Given the entrenched racism, and the clear history of subversion of basic civil rights, Garrity had no choice. Unfortunately, the failure of leadership in Boston, both Black and White, pro-and anti-desegregation, led to undermining Garrity’s decision and the earlier Brown V. Board of Education decision.

References

Garrity, W. Arthur, Jr. (1974). The Boston School Decision: The text of Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr.’s decision of June 21, 1974 in its entirety. Boston: The Community Action Committee of Paperback Booksmith.

Weinbaum, Elliot (2004, Fall). Looking for leadership: Battles over busing in Boston. Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education, 3(1).

Faubourg Tremé and community engagement

Thinking about Faubourg Tremé and also an earlier post about Cooking up a storm gives me a different understanding of community engagement or civic renewal. Sirianni and Friedland (2005), for example, talk about a broad civic renewal movement in the US in areas such as community organizing and community development, neighborhood associations, civic environmentalism, civic journalism, and healthy communities. They also discuss policies that can foster civic capacity building and problem solving.

Although their survey is useful (I use it in my own course on community engagement), three things seem missing from their picture. The most glaring omission is race. Every one of the areas they discuss is deeply imbued with the history and present circumstances of race relations in the US. The very notion of civic capacity building and problem solving can’t be examined fully without taking into account that there is a legacy of oppression and a lack of understanding about how race has shaped American history and policies.

A second omission is history. Much of Sirianni and Friedland focuses on current movements and tools for organizing, all useful, to be sure. But without a grounding in historical precedents it’s difficult to see clearly our way forward. For example, long before the present generation of civic renewal, Jane Addams and colleagues led the way through their work in Chicago on health care, working conditions, literacy, and participatory democracy. Before that, the Paris Commune built social institutions based on liberty, justice, and equality, with a deep respect for learning by all. Even before that, Faubourg Tremé showed how an engaged community could work together to establish effective civic journalism, work toward racial equality, and build a healthy community.

A third area of omission is art. John Ruskin argues that art and culture reflect the moral health of society. Ruskin influenced Jane Addams, who saw that art in all its forms, including crafts, theater, and cultural practices was essential to community and individual development. The importance of art as a means for a community to find shared values, maintain its own history, and to express itself is striking in both the Faubourg Tremé and Cooking up a storm stories as well. I’m not sure that art ought to listed as a civic renewal movement per se, but it does seem crucial to understand more about what it means for civic health and civic renewal.

References

- Sirianni, Carmen, & Friedland, Lewis A. (2005). The civic renewal movement. Dayton, Ohio: Kettering Foundation.

Faubourg Tremé

Just to the Northwest of the French Quarter lies a neighborhood that few tourists visit, and many have never heard of, called Faubourg Tremé. Much of the area now appears bleak with Interstate Highway 10 bisecting it, industrial yards, and boarded up buildings. But it’s one of the most important neighborhoods in American history, and still has meaning for today. There are efforts to restore Faubourg Tremé and to learn what it has to tell us.

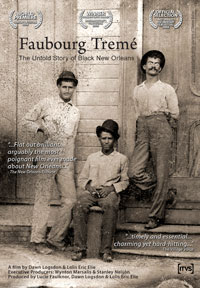

A recent, award-winning documentary tells the fascinating story, made all the more compelling by relating it to the life of a young reporter for the Times-Picauyune. The film is Faubourg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans. Reporter Lolis Eric Elie leads us in his discoveries about his own city. He and director Dawn Logsdon show the relation between the city’s present and its rich past, enlivened throughout by music, including Derrick Hodge’s original jazz score, the Tremé Song by John Boutté, and a century of New Orleans music.

A recent, award-winning documentary tells the fascinating story, made all the more compelling by relating it to the life of a young reporter for the Times-Picauyune. The film is Faubourg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans. Reporter Lolis Eric Elie leads us in his discoveries about his own city. He and director Dawn Logsdon show the relation between the city’s present and its rich past, enlivened throughout by music, including Derrick Hodge’s original jazz score, the Tremé Song by John Boutté, and a century of New Orleans music.

Viewers also meet Irving Trevigne, Elie’s seventy-five year old Creole carpenter, who descends from over two hundred years of skilled craftsmen, as well as Paul Trevigne, editor of L’Union, the first black newspaper in the US. L’Union and later, the Tribune, were strong advocates for the abolition of slavery, but beyond that, for full citizenship and social equality for all blacks, something most northern abolitionists shied away from. They hear from Louisiana Poet Laureate Brenda Marie Osbey, musician Glen David Andrews, and historians John Hope Franklin and Eric Foner as well.

Faubourg Tremé was home to the largest community of free black people in the Deep South during slavery, where they published poetry and wrote and conducted symphonies. It was a racially-integrated community, a model for our own future. It as also possibly the oldest black neighborhood in America, the home of the Civil Rights movement and the birthplace of jazz. (See Congo Square to the right.)

Faubourg Tremé was home to the largest community of free black people in the Deep South during slavery, where they published poetry and wrote and conducted symphonies. It was a racially-integrated community, a model for our own future. It as also possibly the oldest black neighborhood in America, the home of the Civil Rights movement and the birthplace of jazz. (See Congo Square to the right.)

Long before Rosa Parks, Tremé residents organized sit-ins on streetcars leading to their eventual desegregation. But on June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy from Tremé deliberately challenged the Louisiana 1890 Separate Car Act, by insisting on sitting in a whites-only car on a commuter train. He was arrested, tried, and convicted and eventually lost in the infamous Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson. The resulting “separate-but-equal” decision legitimized segregation throughout the US for the next 62 years, and was a major blow to Tremé.

Following later assaults from urban renewal, Interstate Highway 10, and then Hurricane Katrina, it’s surprising that anything remains in Tremé. But one thing that has survived is a sense of history, embedded deep in the music, dance, architecture, social relations, and stories of the community. It is this history which holds a promise for the renewal of Tremé and perhaps of the larger US Society.

The film is a must-see, telling a story that is simultaneously informative, uplifting, and disturbing.